Oblivion Is Not the Answer

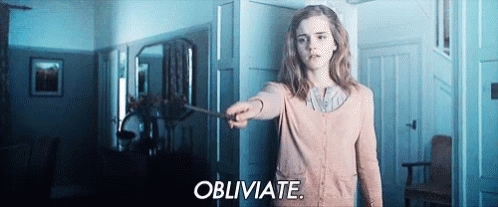

If you type the word “obliviate” into your search engine, the first references are to the charm in the Harry Potter books that causes an individual to forget. For example, Hermione used the obliviate charm to erase her existence from her parents’ memories in order to protect her family in case the Death Eaters paid them a visit.

If you type the word “obliviate” into your search engine, the first references are to the charm in the Harry Potter books that causes an individual to forget. For example, Hermione used the obliviate charm to erase her existence from her parents’ memories in order to protect her family in case the Death Eaters paid them a visit.

For many if not most of us, being utterly forgotten—or utterly forgetting—evokes anxiety, if not terror. Who wants to be consigned to oblivion?

“We got to vote these people into oblivion. (Applause.) Vote them into oblivion. Got to get rid of them. So bad for our country.” So said President Donald Trump, October 10, 2020, speaking from the White House to a “peaceful protest for law and order.”

The upcoming presidential election is a heresy trial. The candidates’ grounding narratives, the understandings of who belongs here, what a proper moral order is, and how to overcome the nation’s barriers conflict radically (derived from a word meaning “at the roots”). I wouldn’t say that “the candidates could not be more different.” But once the division between agendas and visions reaches the width of an unbridgeable canyon, further measurements of difference are irrelevant. What will happen to whomever is branded the heretic?

Politics in the U.S. have taken on the level of “other hatred” and de-humanization that was once reserved for combatants in foreign wars, civil wars, genocide, and religious wars. Forbearance—not using all the power a political group has to humiliate, enact vengeance against, or punish a politically weaker opposing party—is a fading practice.

It feels like a heresy trial is upon us. One needs to look and listen no further than the highest office in the land, along with aligned news outlets, pundits, talk radio, and elected representatives, to see sharp lines drawn between orthodoxy and heresy.

As quoted above, the president recently said, “We got to vote these people into oblivion.” “These people” are Democrats. According to recent polls, over half the nation’s likely voters will cast their ballots for candidates the president said should be voted out of memory.

Oblivion is a harsh, radical word. To be obliviated means being wiped from memory, cleansed from the historical record.

In the word oblivion, I hear echoes of Hebrew Bible texts narrating how one tribe or nation in the ancient Near East sought to wipe the other from the face of the earth in total warfare. The Hebrew word is herem. Kill every one of them; spare no woman, child, or baby. Knock down every monument, every stele. Pulverize the clay tablets or burn the written records. Bleach them out of history. Like they never existed.

Surely, in a democracy that prides itself on the rule of law and individual rights, consigning a person or a people to oblivion should not be an option. But, if we remember the history of white hatred toward indigenous people here, we know the option is real. It has been exercised.

Heather Cox Richardson recently published an outstanding work, How the South Won the Civil War. It is a haunting read. In sum: the southern planter oligarchy was disempowered by Reconstruction. But they regained power by aligning with western settler-colonist-invaders. Reconstruction was subverted in the states with Black Codes, Jim and Juan Crow, lynching and other acts of terror, and voter suppression. And all this was enabled by eastern and upper midwestern elected representatives who allowed the argument of “states’ rights” to rule.

In addition, Edward Blum shows how white northern Protestant religious leaders hastened the “reconciliation” between northern and southern white Christians through offering cheap grace (not his phrase), which is forgiveness without conversion or repentance. The causes of preserving inequality, of advancing white supremacy, and of hallowing the right to take lands found allies—more or less aware allies—among white Christians from Union states. The rhizome of racism remained highly viable in the soil, even as the above-ground stalks had been trimmed back. Richardson believes the present day is second only to the Civil War for demonstrating the power of a political minority racist oligarchy that seeks to rule the majority.

In recent months, I’ve read many social media posts from persons who believe the North should have obliviated the South, that it was a mistake to allow the South to rise again. For those with this opinion, Lincoln’s “with malice toward none and charity for all” was a mistake as wrongheaded as the protagonist in horror movie believing that the vanquished villain is really drowned in that bathtub on the first attempt.

But what would obliviating the South have meant? Should the Union have executed every rebel leader? Should Sherman’s burning of Atlanta and herem-like march to the sea been the model for how the South was treated all over? Should the North have established re-education programs for Southerners, akin to what Germany did after World War II to “de-Nazi-fy” former party members?

So, what does all this mean for the upcoming heresy trial otherwise known as the presidential election? How might a strategy of oblivion be exercised today? One shudders with the thought.

I concur with Dr. Richardson: there is a fierce tension today regarding the fundamentals of the nation we’ve not experienced since the Civil War and its aftermath.

Consigning one group of human beings or another to oblivion is the wrong endgame. Today seems like an opportune time, a critical time, to learn more. To re-member the previously suppressed stories of the nation’s history. To dig out the remnants of obliviated peoples and their stories, for they haunt this nation.

This James Baldwin quote is all over the internet: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

And nothing can be faced until it is seen or remembered. Obliviating will not move “we the people” toward a more perfect union.

See a related post regarding memorials and monuments.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

IMAGE CREDIT: https://harrypotter.fandom.com/wiki/Memory_Charm

Comments are closed.