States are Not Denominations

One expects to be welcomed in different ways and to have different permissions as one visits religious congregations of various Christian denominations and other religions. But should a similar experience await you state-to-state?

If I attend worship at a Missouri Synod Lutheran Church or a Catholic congregation, I would not expect to take communion, which in those places is for “family only.” At Orthodox and Catholic congregations, doctrine categorizes me as a “separated brother” and not in communion with them. However, if I were barred from the table at my own United Methodist Church or at a Disciples of Christ congregation, I’d be shocked.

When attending a Baptist church I would expect to see a pool for a baptistry, for immersing a youth or adult, and not a font for sprinkling an infant. My baptism as an infant may or may not be recognized.

When visiting a mosque, I expect to take my shoes off upon entering. I would expect to keep my shoes on upon passing the red door of an Episcopal Church. And if a Presbyterian Church usher instructed me to sit “on the men’s side,” I’d be as confused as if a Mormon invited me into a temple on a non-visitor day or a Muslim invited me to pray with the women.

Welcomes, permissions, and privileges differ for members and non-members in nearly all religious congregations. This is expected.

But state-to-state?

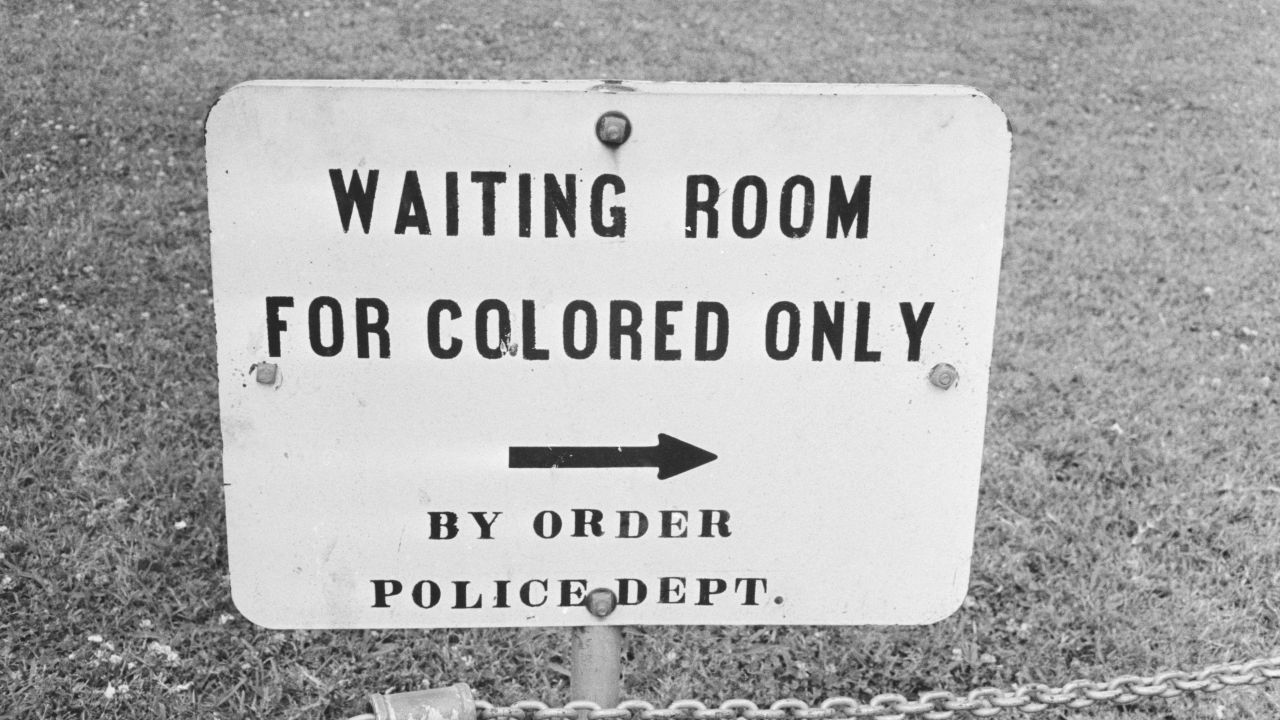

In Isabel Wilkerson’s brilliant book, The Warmth of Other Suns, she traces the stories of several Black families who participate in the Great Migration, who left the South from World War I through the 1960s looking for a better life with more equality of opportunity. (The families found that—sometimes and in part; often they found James Crow.) When describing what Jim Crow segregation involved, she detailed train travel from a legally segregated state to a state where segregation on public transportation was illegal. The example she included was a train coming from Kentucky and going through Cairo, Illinois.

In Isabel Wilkerson’s brilliant book, The Warmth of Other Suns, she traces the stories of several Black families who participate in the Great Migration, who left the South from World War I through the 1960s looking for a better life with more equality of opportunity. (The families found that—sometimes and in part; often they found James Crow.) When describing what Jim Crow segregation involved, she detailed train travel from a legally segregated state to a state where segregation on public transportation was illegal. The example she included was a train coming from Kentucky and going through Cairo, Illinois.

When the train entered Cairo from Kentucky, the cars were segregated by race. The train pulls into the Cairo station. There is another train waiting. All the passengers must disembark from the segregated train, walk over to the awaiting train, and take their seats in racially integrated cars.

This story was new to me. I was taught long ago that Cairo is no pocket of racial harmony and shares more attitudes with the Old South than with the allegedly less-prejudiced North. So, I did not think of Cairo as a place where segregation gives way to integration. But Cairo is in Illinois, where integrated public transportation was a legal right. The bigger “newness” in this story is being introduced to one significant way in which passing from state to state during Jim Crow used to be anything but seamless.

When rights vary by state, traveling from state to state is like moving from one country to another. Moving to live in a new state may well involve a change in rights.

As one raised in the Chicago area, I was never asked to pledge my loyalty to my state, as far as I can remember. We recited the pledge every morning in public schools—to the United States of America.

I did not pledge loyalty to the State of Illinois and would not have done so if asked. I have not and will not pledge loyalty to the State of Oklahoma.

In terms of understanding the nature and origin of my rights, I always thought of myself first as a citizen of the USA. I think first of the Declaration and the Constitution. Up until very recently, I saw the federal government and the Supreme Court as allies in the work of ensuring citizenship rights, of widening the circles of equality and justice to include individuals and categories of person who were previously excluded or, in some way in their states, treated as “lesser than” or as unwelcome persons. That work of extension and expansion was often a counter to the mantra of “states rights” which nearly always seems to mean “in my state we have the right to discriminate.”

As I respect the variety of practices between religions and among denominations, I love the different state mottos. The show me state. Eureka. Land of Lincoln. It is enlightening to learn the histories of different states as well as their current customs and ways. When I lived in the D.C. area for a few years, I always smiled when I saw the Maryland sign “Please Drive Gently.” In understanding Virginia, I had to learn what a “glebe” is (the equivalent of country but with an origin in property supporting a Church of England priest’s living, often by growing tobacco). From state to state, I expect differences in customs, foods, whether or not I’m called “hon” in a grocery store or restaurant, accents, and some mores.

I do not expect and should not expect rights to be different, state by state. Rights are legally protected permissions to do something or not to be forced to do something. They are linked to responsibilities and duties. They are derived from normative understandings of what it means to be human. They are supposedly to be recognized and protected by governments rather than granted by governments.

Turning states into something akin to sovereign denominations is a terrible, harm-full idea. Are we headed toward a nation in which crossing a state line will mean being stopped by an official who commands, “Papers, please?”

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Comments are closed.