Nativity Politics

Occasionally I hear from laity or clergy concerning discussing politics in church. Of course, who would want to use worship, a ministry meeting, or a church school class to replicate a polarized, contentious go-nowhere storm of words and emotions? No one. But we should be very careful about broad statements concerning church and politics. On the one hand, barring political matters from religious life means the weighty moral issues of the day are met with spiritual silence. (See my blog on that topic.)

On the other hand, prohibitions on politics in church would also mean that we’d ignore not just a single elephant in the room of scripture, but a massive herd.

For example, take the two nativity stories in Matthew and in Luke. Both stories are saturated in political drama. Both stories reflect the politics of living in cantankerous province of the Roman empire. Ignore the politics of the story and one remains ignorant of their meaning.

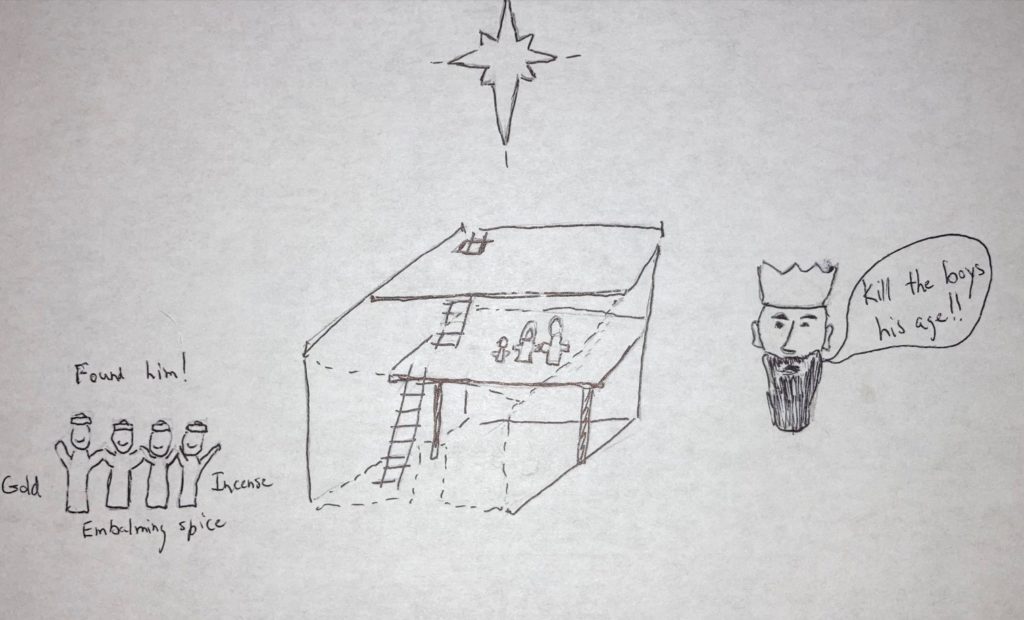

In Matthew, Jesus is born at home in Bethlehem, the city where God’s anointed was to be born. A star appears, as stories also claim happened at the birth of Caesar.

In Matthew, Jesus is born at home in Bethlehem, the city where God’s anointed was to be born. A star appears, as stories also claim happened at the birth of Caesar.

When Herod, the Roman-appointed King of the Jews learns from the magi that a King of the Jews has been born, Matthew says that Herod was troubled “and all Jerusalem with him.” No doubt, for this newborn king would cause heartburn for Herod, his patronage appointments, and the Romans. And the Romans did not ignore heartburn brought on by this gods-denying people. So, according to the story, Herod, not knowing which particular child was his rival, echoes Pharaoh—who may have been history’s original “Jews will not replace us” leader, for Pharaoh feared if his enslaved population grew too large, they would rebel.

Pharaoh was eventually undermined by Moses, the baby who got away. So, to avoid Pharaoh’s fate, Herod gave a blanket order for soldiers to slaughter all children under two years old. Except one toddler got away… His parents took him to Egypt for safety. One should not miss the wonderful interplay of political references and meaningful reversals of where safe harbor might be found.

No politics in any of that, right? Actually, ignore the politics in the story and one cannot understand the story in its context nor use it to interpret our lives today.

In Luke, we get a lengthy run-up to Jesus’ birth. One storyline follows Zechariah, Elizabeth, and the birth of John, the one who would become John the Baptizer. Read Zechariah’s testimony at the end of Luke 1. That speech is full of references to the one who will rescue the people from their enemies. Zechariah is not addressing humanity’s inner demons but liberation from his people’s occupying overlords.

Then there is little, humble, quiet Mary—except that one cannot read the words we’ve come to know as the Magnificat and allow such diminutives to depict Mary. Mary mightily prophesies that her son will save the people from their enemies, bring down the powerful from their thrones, send the rich away empty, and fill the bellies of the hungry. Geez, socialism, obviously. I don’t know how politics-in-church allergic choirs sing the Magnificat in Handel’s “Messiah” without breaking out in hives.

After receiving these revolutionary messages, Luke’s readers then learn an imperial census, a prelude to a tax levy, will cause him and his very pregnant wife to travel to Bethlehem. An imperial demand for more money from the enemies her son would undermine caused Mary to give birth in a stable.

If one filters out the politics in the birth narratives—and in SO many places in the Bible (we could go into the language of referring to God as King, and the classical prophets do not make sense without a king and ruling class to speak against)—one both distorts the meaning of texts and impoverishes the churches’ capacity to address today’s politics with moral and spiritual power.

Silence is not always golden. Sometimes silence makes matters worse.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Comments are closed.