Maybe a Little Hell Could Be Good

There was a time when the point of evangelical sermons was to scare the hell out of people and frighten them into heaven. If people were not uncomfortable to the point of feeling the war in their souls between God and Satan, the preachers were not doing their job.

Now a branch of the political and spiritual descendants of these evangelicals is working, state by state, to make sure their children are not discomforted by the “hell” of what they learn in school.

Evangelicalism was, of course, not always primarily a political identity most associated with predominantly white and historically Southern denominations in the U.S. While one can find strands of evangelicalism (and just about everything else) in the Bible, evangelicalism emerged as a distinct understanding of how one becomes and remains a Christian during the Protestant Reformation. Evangelicalism centered on the authority of scripture over tradition and on the personal experience of the “for me” of the promise of God’s grace offered in Jesus Christ.

Here in the U.S., especially during the opening decades of the 19th century, mass religious meetings—camp meetings—developed. Camp meetings evolved to maximize the evangelical experience of conversion. Those meetings, often in wooded or “wilderness” settings, lasted from a few days to two weeks. Attendance could exceed thousands. The larger meetings featured multiple preaching platforms. Day and night, preachers held forth.

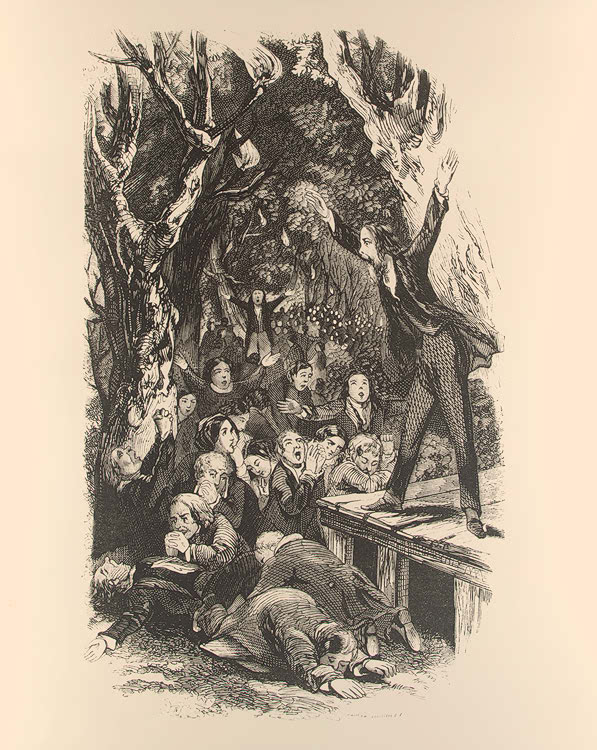

Lorenzo Dow preaching, engraving by Lossing-Barrett, 1856

The best preachers were reserved for night. In the wilderness, it was believed, the devil is strongest, confrontations between God and Satan most powerful. At night, with torches flickering around the camp, preachers did their best to scare up visions of hell. One well-known, very weird, preacher was Methodist Lorenzo Dow. “Crazy Larry,” as his colleagues called him, would bring people news from their relatives in hell!

The point was to scare people into seeking salvation NOW. Preachers used every rhetorical trick and physical manipulation to make people uncomfortable enough to seek relief. No relief would be available to the people without a painful confrontation in their souls and bodies.

The techniques and some of the physical pieces of camp meetings were adapted for congregations. Hell was a prominent theme in sermons until the early 20th century, in the mainline church (which is one branch of evangelicalism), and long after that in southern evangelical and some Catholic congregations. (When the movie, The Exorcist, was released in 1973, some religious commentators mused that when the churches gave up preaching about the devil, Hollywood found there is still a very substantial audience.)

The standard evangelical sermon ended with an altar call for those who felt “convicted.” The mourner’s bench, a front pew in some churches, is where the saints-to-be could be surrounded in prayer until Jesus triumphed.

In traditional evangelicalism, good news is first received as bad news for the sinner. “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound, that saved a wretch like me! … ‘Twas grace that taught my heart to fear and grace my fears relieved…”

Today, legislators in multiple states, working from the same playbook, are passing laws to prohibit white children (not stated as such but that is the group clearly being “protected”) from being discomforted by America’s racial history or the claim there is systemic racism now. No exposure to the hell to which “others” in the U.S. were and are subjected.

How completely un-evangelical.

Grace first teaches our hearts to fear. Grace first opens our eyes to the moral and material gap between what is and what should be. Only after that discomfort, and repentance, and acts of repair can a person—or a society—find salvation.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Comments are closed.