Immoral Freedom

When Amazon founder and multibillionaire Jeff Bezos returned from his brief trip into space aboard his own rocket, he said: “I want to thank every Amazon employee and every Amazon customer because you paid for all of this.”

Pause.

“Thank you for working almost as fast as the robots I will one day replace you with, and for buying stuff from both legit and illegitimate manufacturers as I do my best to drive every seller of every item on the planet into my website.”

This fictional sentence I just composed is about as moral as what Bezos said. Fundamentally, he thanked everyone for giving him the freedom to do something that very few persons on the planet can do.

When freedom is not reciprocal, when freedom is not mutual, when my freedom depends on your lack of freedom, then my claim to freedom is immoral.

We Americans are transfixed on freedom. Those of us who call ourselves Christians resonate with biblical stories such as the Exodus (or at least the liberation and conquest parts; the wilderness testing—not so much) and “For freedom Christ has set us free. Stand fast therefore and do not submit again to the yoke of slavery.” (Galatians 5:1) Never mind the context, that Paul is talking about circumcision.

But what do we think about equality? Are we as in love with equality as we are freedom? No. Not even close.

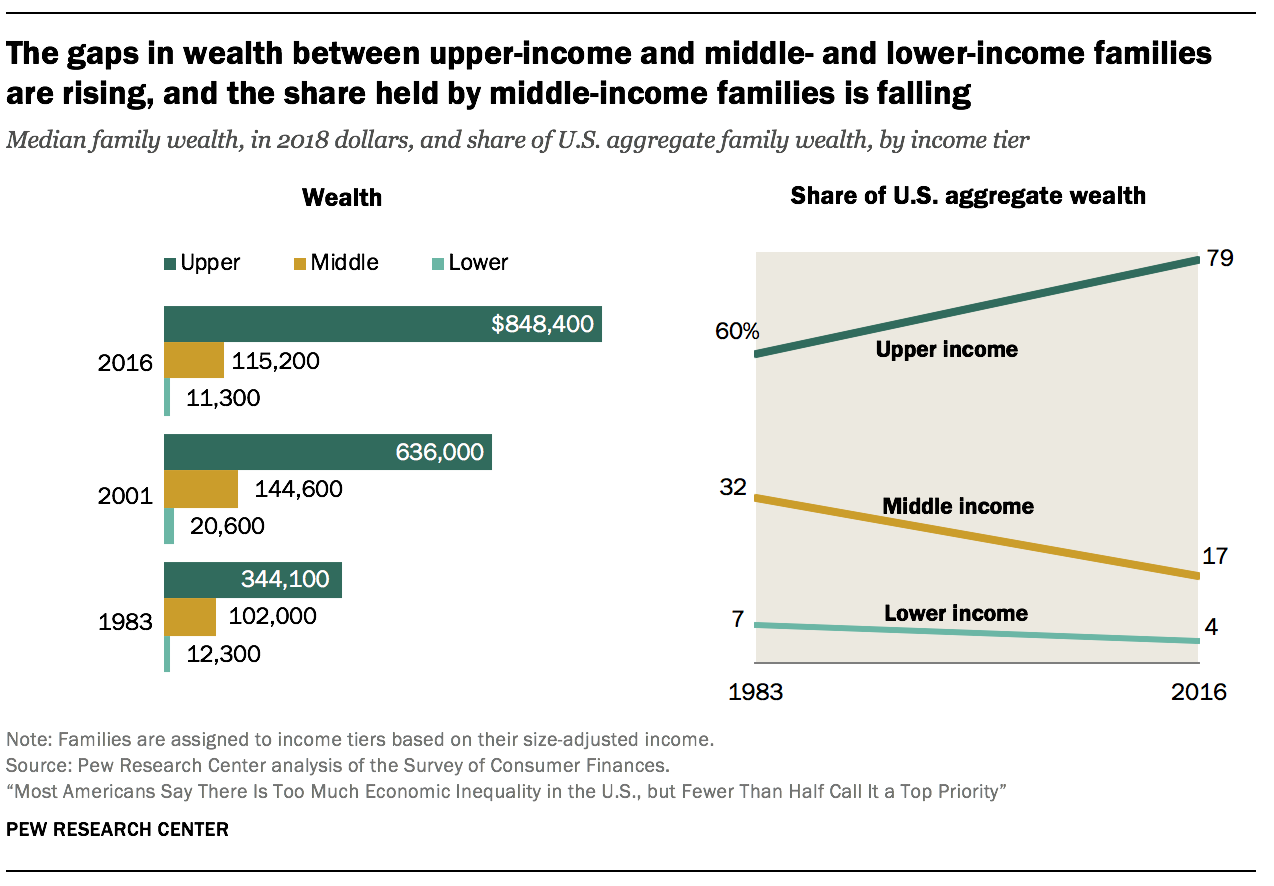

We tolerate, and even deepen and widen, inequalities in our nation. Look at this one graph (pre-pandemic) from Pew Research:

For anyone claiming these figures represent a working meritocracy, I have pieces of the true cross and Noah’s ark to sell to you. I keep thinking of the powerful song from the musical 1776 in which Carolinian John Dickinson proclaims: “Don’t forget that most men with nothing would rather protect the possibility of becoming rich than face the reality of being poor.”

The graph shows what the (un)godly market has wrought, and the numbers look even worse in terms of inequality if one compares Black to White Americans.

We claim to embrace the line from the Declaration that “all men are created equal” despite the limited “original intent” regarding to whom “men” and “equal” applied. We salute the words of the Gettysburg Address: “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” And we parade out Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s legacy and words annually—although the words-of-choice are often so redacted that “the fierce urgency of now” is all-but-extinguished. (Aside: as I watched the MLK parade in Tulsa yesterday, I had a visceral reaction to one entry from an organization that in this state stands for just about everything Dr. King opposed.)

In current political battles, equality is a particularly loaded word (and I won’t go to “equity,” which may be even more incendiary). Any social policy dealing with inequality that involves taxing the wealthy to create more opportunity for the poor is considered immoral by some. The word equality, along with words like “community” and paying attention to unsustainable and destructive inequalities, brands one a socialist or communist. Champions of equality are accused by opponents: “You want to take away from me money I earned and give it to people who did not work for it and don’t deserve it. That’s immoral.”

Declaring a nation based on quality of opportunity (“if you work hard…”) within a system established and defended to protect inequality creates conflict, and maybe even war. The chasm between words and realities fosters anger on one side of the divide. Attempts to narrow that chasm evoke anger on the other side.

Here is the moral dilemma of freedom yoked to equality. When equality is yoked to freedom, freedom cannot mean doing as one pleases without regard for the freedom of others. Said more plainly: equality yoked to freedom means my freedom is limited by your freedom, and vice versa. Freedom is not an absolute—and neither is equality. No right or condition is absolute.

One could say that America is a continuing story of how the moral dilemma of freedom-equality will play out and whether or not we are indeed dedicated to the proposition that all persons are created equal and free.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Comments are closed.