Help Me Plan Public Ceremonies of Grief and Lament

The most recent statistics are these. Worldwide, while the official death total is around 6 million people, it is estimated that up to 20 million people have died from COVID-19. In the United States, given that we have surpassed 900,000 official deaths, it is probably fair to estimate the total deaths from COVID exceed 1,000,000.

Some of these deaths were surely not preventable. Some of them surely were.

How does that song from the musical Rent go? “529,600 minutes, how do you measure, do you measure a year?” Twenty-million deaths in such a short period of time represent millions and millions of lost years.

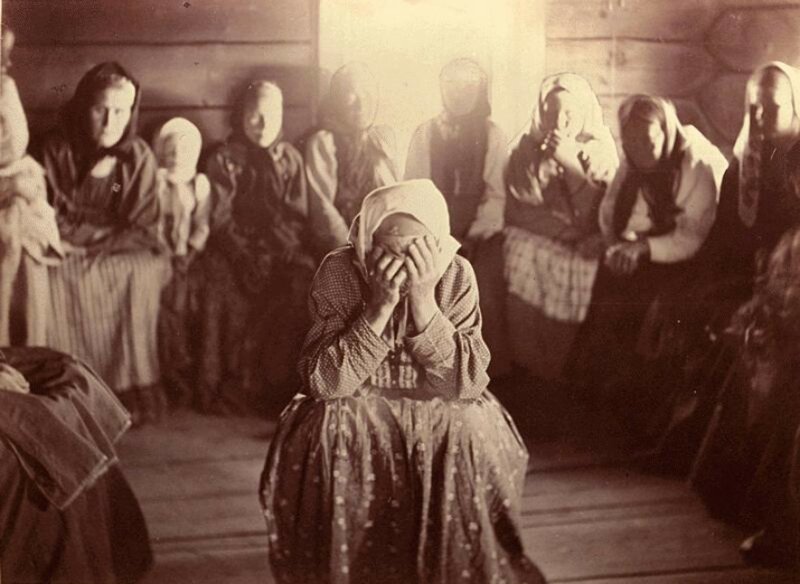

That loss needs to be grieved and lamented.

Add to the deaths dozens of other kinds of losses. The loss of health plaguing those with long COVID. How many children have lost one or both parents? How do you measure the loss of a parent? The loss of normal rituals when a loved one died. Workers from store clerks to teachers to restaurant servers to flight attendants to all levels of medical personnel experienced burnout, insults, profoundly ignorant and abusive behavior, and even assault and deadly violence. Why? Simply because they said “Please wear a mask,” or they were in the wrong place at the wrong time and someone decided to take out their anger on the next person they met.

Add to the deaths dozens of other kinds of losses. The loss of health plaguing those with long COVID. How many children have lost one or both parents? How do you measure the loss of a parent? The loss of normal rituals when a loved one died. Workers from store clerks to teachers to restaurant servers to flight attendants to all levels of medical personnel experienced burnout, insults, profoundly ignorant and abusive behavior, and even assault and deadly violence. Why? Simply because they said “Please wear a mask,” or they were in the wrong place at the wrong time and someone decided to take out their anger on the next person they met.

So many people, both individuals and even whole industries, should be raised up as heroes. In once-upon-a-time normal times, the scientists and public health officials and delivery systems and drivers would be. But these are not normal times.

What is happening and what will happen to our society if we do not grieve and lament our and the world’s profound losses?

Nothing good.

We in the United States cannot expect our elected leaders to lead in creating moments and memorials for grief and lament. There would have to be way too much dealing with reality and with each other as human beings, both of which are in critically short supply among those who have been elected to lead—as well as in the general population.

In the past, we in America have often turned to our religious organizations to help heal self and other-afflicted wounds. I don’t know if we, as a people, are of a mind to make that turn in any substantial way this time. Nevertheless, the nation collectively and we in our communities locally need opportunities to grieve and lament.

While the culture of our day has demonstrated that anything can be made political, grieving is going to be seen as less political then lamenting. To lament means to deal with a loss that was preventable, a loss from which we cannot shirk our responsibility and culpability. To lament is both to feel the pain of a loss that did not have to be and to realize that our own behavior contributed to bringing the pain upon ourselves. Thus, one can see that lament implicates our choices, assumptions, and prejudices.

For some months now, I’ve been considering what kind of public ceremony I might help to develop in and for the greater Tulsa community. I’ve consulted with some clergy friends and other caring professionals. As we’ve experienced waves of COVID that have delayed larger gatherings, it has been difficult to plan and calendar a ceremony or a series of ceremonies.

Imagine with me, please. I imagine a gathering at a place like Guthrie Green. At nightfall. Each attendee brings something to represent the loss they and their family experienced during COVID: a picture, an article of clothing, a coffee cup no longer used. Candle lighting. Poems of lament. Music such as Barber’s Adagio played on a solo cello. Songs of grief from our religious traditions. And some room made to thank those who have been performing throughout the pandemic with professionalism and compassion. I can imagine one service, and I could also imagine a series of services, such as one expression of lament and grief on every Monday at noon or dusk for a month.

I reach out to you, the regular readers of this blog, and ask for your opinions and your help. What community expressions of lament and grief what you find most helpful? What might draw you out of the comfort and safety of your home on a summer or fall evening to gather with others for the essential work of grief and lament?

Leave your comments on Facebook or email me at crpl@ptstulsa.edu.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Comments are closed.