On Taking God’s Name in Vain in Public

With our behavior, Christians have sullied good words over time. Evangelism should mean “good news” rather than aggressive proselytizing. Missionaries have been colonizers and imperial agents. Evangelicalism is in danger of being a zombie for political identity.

And then there is the word “God.”

Of course, God’s name—any one of God’s names—has been invoked since before history and assigned praise and blame for everything from earthquakes to elections, from winds to wars, from accidents to anointings.

Has this prolific or profligate invocation of God been truer anywhere than in the United States?

A community friend recently told me about a meeting in which a local pastor declared God wrote the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Not the other amendments, solely the Second.

Whaaaat?

A cohort of Christian leaders and influencers trumpet the prior president as God’s anointed, akin to either the flawed King David or the pagan Cyrus who liberated Israel from its captivity (in the U.S., the claim is that the president liberated evangelical Christians from the captivity imposed by the previous administration).

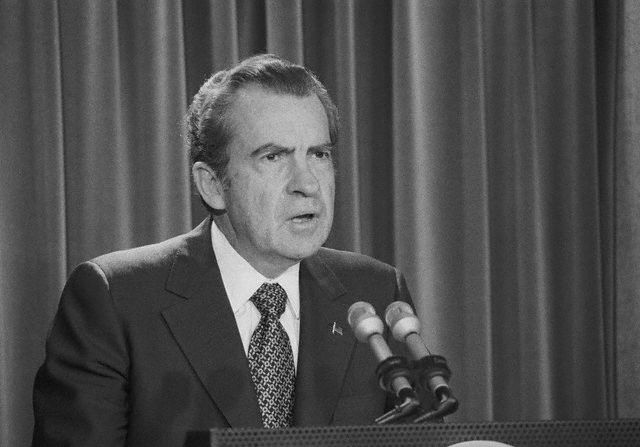

I am somewhere between sick and tired of candidates for elected office in my part of the nation declaring that God told them to run for office. Can you imagine a president returning to the pre-Nixon years and omitting “God bless America,” or similar words, from the end of their speeches?

I am somewhere between sick and tired of candidates for elected office in my part of the nation declaring that God told them to run for office. Can you imagine a president returning to the pre-Nixon years and omitting “God bless America,” or similar words, from the end of their speeches?

Personally, I admire and want to promote the national motto, e pluribus unum. The official motto, “In God We Trust,” printed on our carriers of value (money), was supposed to differentiate godly Americans from godless communists. Given the power of the U.S. in the world’s markets and military conflicts, I’ve never been sure what trusting in God means for a nation with so much power. Nevertheless, state legislatures are requiring schools to plaster the motto in every classroom.

All this has led me to wonder: what would happen if we in the U.S. invoked God less often in public life?

There is an ancient theological tradition called apophatic theology. Since who and what God is cannot be captured in words, since every representation of God is partial, then it is just as important to name who and what God is not as it is to make affirmative claims.

God is not king (or queen). God is not an emperor. God is not a president. God is not a mother or father. Saying “God is not” does not cancel everything about claims regarding who God is, that God may have some of the attributes we know from human leaders. But apophatic theology reminds us to hold our claims loosely.

What if God does not have candidates, does not determine the outcome of elections, does not anoint kings? Yes, the Bible contains plenty of call stories for prophets and kings, for judges and tribal leaders, for a Christ and his followers. But what if we in the U.S. are now in a perpetual state of conflict, another expression of the oldest form of hate and murder—fratricide—because, in Abraham Lincoln’s words (Second Inaugural Address):

Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any man should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered ~ that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.

The Civil War may have been a different battle if neither side would have claimed God on their side. Claiming God’s imprimatur elevates one’s cause to the highest level and, not ironically, can result in the most vicious violence in the name of “all that is holy.”

Western Christian theology has been too oriented toward understanding God in the context of human history and governance. Our theologies, my own very much included, have been puny. We have not embraced the realities of a nearly 14 billion-year-old universe, at least five mass extinction events on earth, countless potential lifeforms elsewhere, and the fact that humankind belongs to the earth and not the other way around. Who is this God in whose creation dinosaurs dominated the planet, or where a solar flare could disrupt life as we know it, or in whose universe life is undoubtedly teaming?

Not emperor. Not king. Not father. Not. Not. Not.

In a counseling session some decades ago, the counselor listened to me detail a relationship that troubled me. At some point, the counselor looked up from his clipboard, put down his pencil, and stated: “With everything going on in the other’s life, you know, you are not the center of their drama.”

I wonder how often we put ourselves at the center of the universe, at the center of God’s drama—and we are not. Our problems, our elections, our battles. Important to us but not the center of the universe’s attention.

As is said in Taoism, “The Tao that can be named is not the Tao,” so with Christian naming of God. When we think we know who God is and what God is doing, we are sure to be at least partly wrong. Claiming God’s approval can be a form of taking God’s name in vain.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Comments are closed.