Which Myth Comes After a City on a Hill

In religious studies, “myth” does not mean “not true.” A myth is not history, as today’s historians try to write history. Names, dates, an observable sequence of events. Rather, to say it paradoxically: myth is about the meaning of life that plays out again and again, that makes sense of the data of our lives.

Myths proffer archetypical stories that play out in history. Regardless of the historicity of the biblical Exodus event (Red Sea or Reed Sea, shallow or deep water, hundreds of people or Cecil B. DeMille’s cast of thousands), the mythic truth of a God who hears the cries of the oppressed and sides with them against the gods who are served by social hierarchies and empire plays out in history again and again—for those who put their faith in that myth.

Somewhere I read about a wise old Southern preacher who was asked where the Garden of Eden was. In reply, he gave his home address where he lived as a kid. The person who queried him retorted in surprise, “I thought it was somewhere in Mesopotamia.” The preacher replied: “Well, all I know is that at 1234 Mayberry Place (I’m making up the address here) when I was 10 years-old I stole candy from a store and ate it in hiding. I felt so guilty. My mother came looking for me calling out, ‘Where are you?’” A true story, yes. A story given meaning by a myth that plays out again and again.

Among all the many challenges facing the U.S. as a nation—and, regardless of your perspective, we can all name a legion or two—is the challenge presented by a national myth that is incapable of serving as our archetypical story moving forward. Manifest Destiny. American exceptionalism. Christian nation. New Israel. Promised Land. As a city on a hill. The myths invoked by these words and phrases—and the legitimated culture, behaviors, and policies—do not ring true to an increasing percentage of the nation.

The good news is that myths can change. We know this because they have changed. Manifest Destiny was declared by a newspaper editor in the 1830s who advocated for taking Texas from Mexico. American exceptionalism may originate with Alexis de Toqueville, a Frenchman who traveled the U.S. also in the 1830s. (Or with Marx! Marx thought the U.S. was exceptional in not developing a proletariat the way his model predicted it should.)

Religious claims about particular colonies, e.g., Puritan Massachusetts, were not shared by all the colonies; and even those colonies such as Pennsylvania and Rhode Island founded on religious visions did not share the same visions. The Pilgrims were not much remembered in U.S. until centuries after they landed (and the stories we 60s children were told about them were myths passing as history). Virginia, and not New England, was the mother of four of America’s first five presidents and was much more influential in the first decades after the Revolution than was New England.

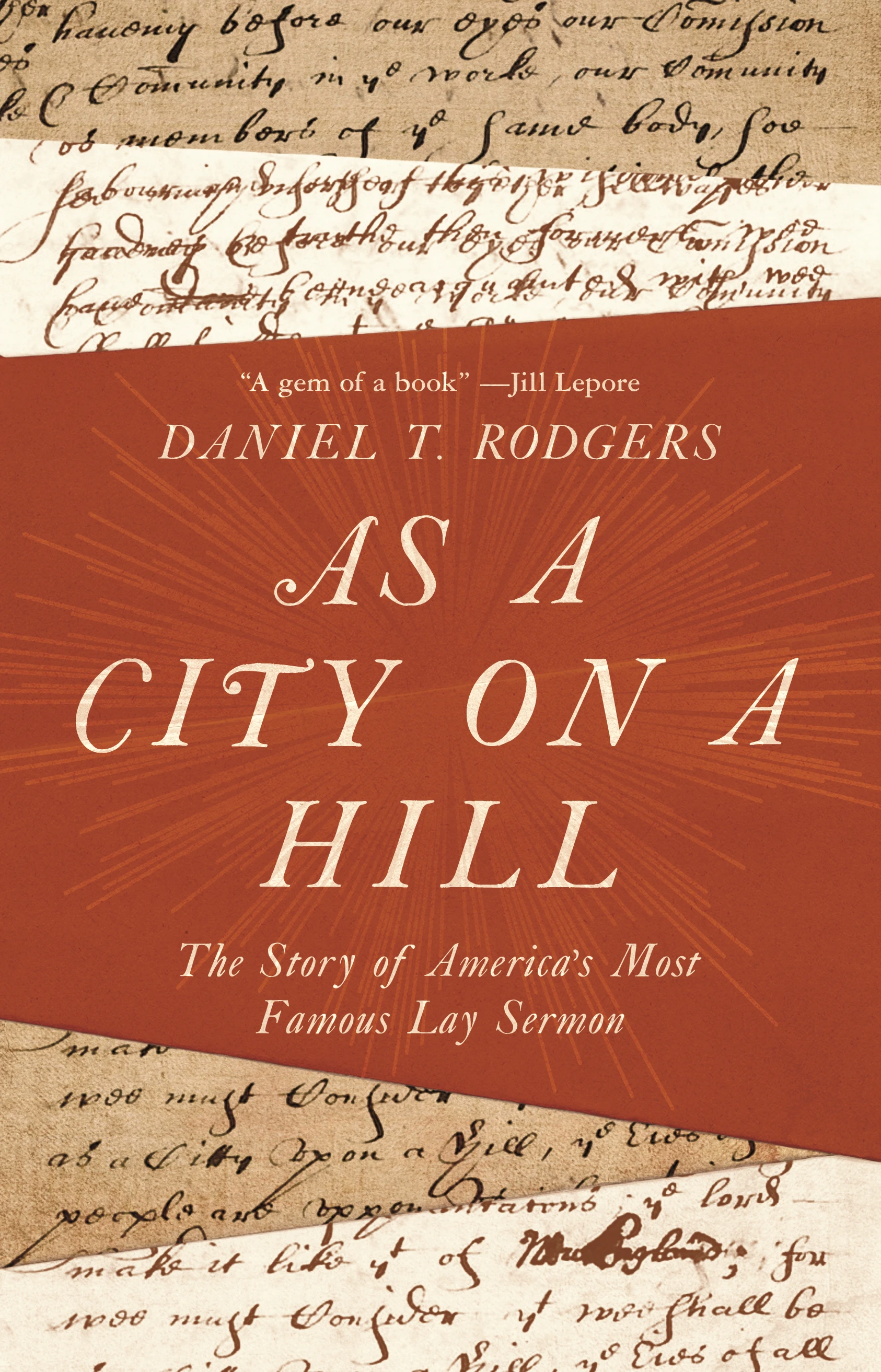

Consider that phrase “as a city on a hill.” This is a phrase from a “sermon” entitled “A Model of Christian Charity,” written by John Winthrop, first governor of the Massachusetts colony. Daniel T. Rodgers wrote a (for me) page-turning, eye-opening history of the use of this writing—and its utter neglect for nearly 200 years after its composition.

Consider that phrase “as a city on a hill.” This is a phrase from a “sermon” entitled “A Model of Christian Charity,” written by John Winthrop, first governor of the Massachusetts colony. Daniel T. Rodgers wrote a (for me) page-turning, eye-opening history of the use of this writing—and its utter neglect for nearly 200 years after its composition.

Winthrop’s original purpose was to plead for the rich associated with the colony to remember their duty to those who are poor. Mentioned only occasionally until the middle of the twentieth century, the image—the myth—became foundational history for Ronald Reagan, for whom it meant promise more than the peril of potential failure.

Rodgers on the history of the myth:

Most likely “A Model of Christian Charity” was never delivered as a sermon at all. Although copies of Winthrop’s text circulated in England during his lifetime, by the end of the seventeenth century they had all literally vanished from memory. One of the long-forgotten copies was discovered in a bundle of old sermons and documents of New England history in 1809, but it was not put into print until 1838. And then it lapsed from sight again almost as completely. …Through the 1970s mention of “A Model of Christian Charity” was a hit-or-miss affair in standard histories of the United States. It was only in the decade of the 1980s, three hundred and fifty years after its writing, that the incongruously parallel work of a conservative Cold War president, Ronald Reagan, and a radical, immigrant literary scholar, Sacvan Bercovitch, combined to make Winthrop’s text and metaphor famous. “A Model of Christian Charity” is old, but its foundational status is a twentieth-century invention. (quote from pp. 4-5)

Winthrop thought he was writing primarily to the colony’s wealthy backers, and to the colony’s wealthy citizens, regarding their special obligation as people of wealth to those who are poor. He used the “as a city on a hill” (the word “as,” by the way, is entirely important to evoke God’s promise to Israel without claiming to be the successor to that promise) to say: Pay attention! Everyone is looking at us. If we don’t succeed, God and the world will judge us harshly.

Claiming a special blessing without special responsibilities to each other and thinking of the whole history of the nation as one shining city on a hill: no, that was not Winthrop. That was a myth divorced from Winthrop’s context, a myth that fundamentally changed his meanings four centuries after his time in order to serve a nation battling both an “evil (atheistic) empire” abroad and progressive, multicultural advocates at home.

One of the opportunities with myth-making in a nation as young as the U.S. is that our history is so recent. Excellent historians such as Rodgers render a huge service by untangling history from myth. Their work gives all of us the opportunity to discard myths that no longer serve their role of providing meaningful story arcs to aspire to and to live within.

From a faith-based point of view: the moral burden of discarding the old myth that privileged a specially blessed city on a hill and choosing a new myth for a multicultural democracy that needs to be a new kind of world citizen is laid upon us. It is a heavy burden, and the eyes of the world are indeed watching.

(Note: much of the historical material in this article is derived from Rodger’s book.)

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Comments are closed.