Forty Years of Change, or Not, in Church and Culture

As I near retirement from my full-time work (January 31), I’ve been reflecting on what has changed—and not—over the 41 years of my post-seminary ministries in congregations and graduate education. Here is a sampling of my thoughts about Protestant churches and social issues over the last four decades.

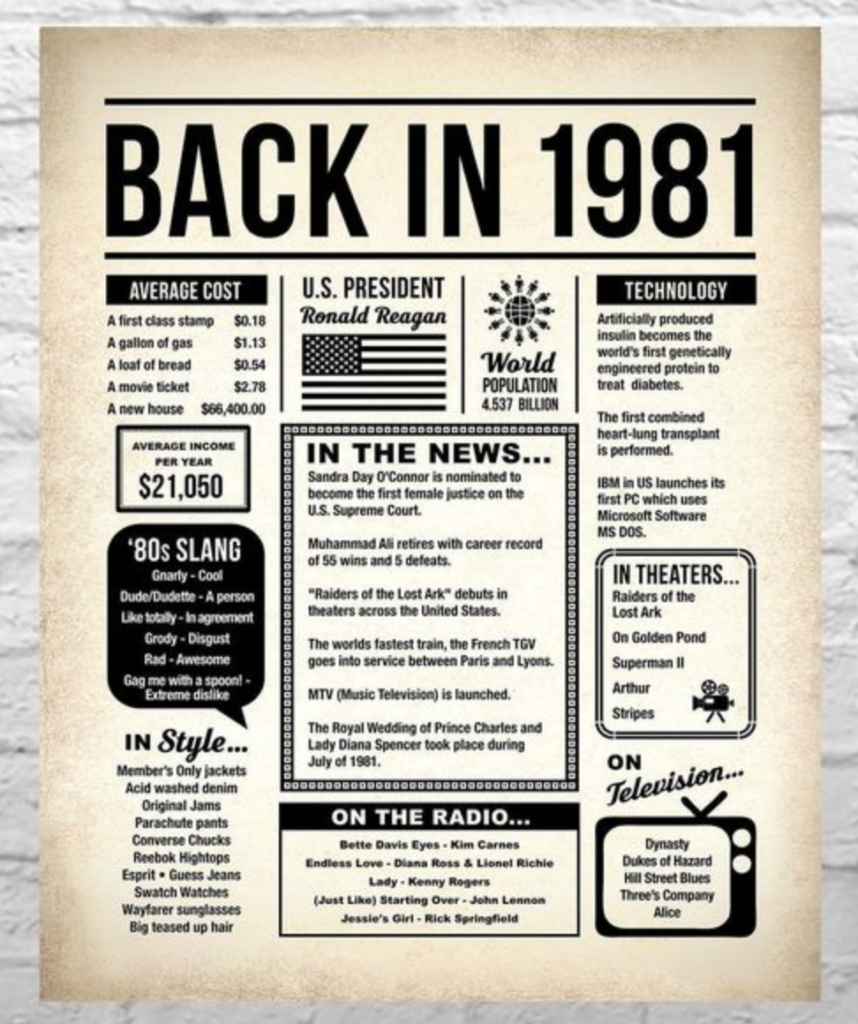

In 1981, America was majority white, Christian, and Protestant. Today, the nation is no longer majority Protestant. If trends continue, the Christian majority will pass in about 20 years. And, depending on how one defines “white” and “non-white”—which are terribly imprecise terms derived from racist premises—the majority of the nation will no longer claim the designation “white” at about the same time as the Christian majority passes. Today, these trends challenge every community whose place in the social order is changing (which is all of them) to re-think themselves. That is hard work, regardless of whether a demographic is “rising” or “descending.”

In 1981, America was majority white, Christian, and Protestant. Today, the nation is no longer majority Protestant. If trends continue, the Christian majority will pass in about 20 years. And, depending on how one defines “white” and “non-white”—which are terribly imprecise terms derived from racist premises—the majority of the nation will no longer claim the designation “white” at about the same time as the Christian majority passes. Today, these trends challenge every community whose place in the social order is changing (which is all of them) to re-think themselves. That is hard work, regardless of whether a demographic is “rising” or “descending.”

The shrinking of mainline congregations is part of much larger trends and can’t be pinned simply on internal factors. The mainline was, significantly, formed by cultural forces and is being dismantled by cultural forces. In the 1980s, many liberals alleged the numerical decline should be pinned on faulty leadership. Indeed, mainline churches often were really lousy at either evangelism (an embarrassing practice from a bygone era) or just welcoming new people.

But a very significant segment of the culture, especially European-heritage cultures, was disconnecting from religious communities. Church opposition to abortion, women’s roles and rights, and issues related to sexuality did divide. But it took us all some time to reckon with the phenomenon of “I’m just not interested.” In 1981, the sound of the word “none” was spelled only one way: nun.

In 1981, churches did not want to sell their property as they shrank. Today, the biggest asset many churches have is the commercial value of their property—or the ministry value of their property for matters such as affordable housing.

“Leadership” was a dirty word in seminary in 1981. It implied white, male, and hierarchical. The preferred word was “enabler.” Since then, leadership has become THE word for what is needed or lacking, albeit not limited to white, male, hierarchical models. And “enabler” is now the dirty word.

Political rhetoric was plenty hot then and now. The so-called “big sort,” of Reds and Blues sharpening the lines between them and moving to places (cities or suburbs or small towns) to be with like-minded people, was just underway in 1981. There were still moderates in both major political parties.

But the political morality of the Reagan years polarized the nation: increasing defense spending, aligning with religious conservatives, implementing the Southern Strategy (such as substituting “welfare mother” for “Black”), and dismantling the New Deal and Great Society forms of government. Liberals (the preferred term at the time; “progressive” was still associated with the early 20th century political movement) hated Reagan’s policies, and some liberals hated the man.

But all that was before the internet, social media, and semi-automatic weapons carried by civilians in public. Yes, polarization today IS worse than in 1981.

As many commentators have said, doing church in pre-internet days was based primarily on assumptions from the worlds of oral and print communications. The revolutions that accompany digital communications and spaces are, in 2022, probably near their beginning. More disruption of those print and oral cultures, in favor of visual-emotional-immerse experiences, to come.

From a liberal or progressive perspective, justice issues have multiplied and become ever more complex. I think nearly every issue, from climate change to racism to inhumane incarceration to trans-rights, was around in 1981 (not at the same level, e.g. the Three Strikes Law had not yet swelled prisons). But the matrix of them—and acting on the matrix of them for a person or community who wants to be “on the right side of history”—is not without its contradictions and proffered hierarchies of claims. Talk to leaders and members of any community that claims to be “inclusive” to verify the difficulty, if not impossibility, of claiming that attribute.

That said, in 1981 marriage equality as the law of the land was unthinkable. “Race” in the dominant culture still meant black and white (except in Southern border states). Today’s complexity is daunting but necessary. And the relationship between justice matters will continue to morph.

All of my ministry years have been influenced by the presence of the Religious Right in public life. The Moral Majority. The Christian Coalition. Praying away hurricanes and declaring 9/11 was caused by liberals, feminists, and gay people. The Tea Party. Christian Nationalism. Liberty University and Hillsdale College. As I’ve argued previously, there is a religious left but it is not a parallel to the Religious Right. Funding, institution-building, focus on pipelines from home schooling through federal judges, news outlets, and alignment with allegedly God-picked politicians all make the Religious Right many orders of magnitude different from a religious left.

I did not hear anything about white Christian nationalism in 1981. That ideology was around but it did not have the public traction it does now. That movement now threatens the integrity of Christianity and the very being of the nation.

Nuclear war was the greatest global fear then. Climate catastrophe is the biggest one now. But, even in 1981, when the U.S. and the Soviet Union acted from the “strategy” of mutually assured destruction (MAD) and each side could rain so many bombs on the other that each could “make the rubble bounce,” immediate loss of life was one concern. Rendering the planet uninhabitable was the other. And, it was controversial to bring up nuclear war in a sermon. Almost every congregation was populated with persons who voted for both parties.

And today, nuclear war again joins climate change in our worries

Battles over how to interpret the Bible regarding gender and sexuality issues were newer in 1981. Not new, but newer. Now the issues have ripened into church -dividing issues, as evidenced by multiple Christian denominations. It may be quite a while before “blessed be the tie that binds” feels like a blessing again.

Several big positive differences between then and now: women and queer persons in leadership, cross-racial and cross-cultural appointments and calls, re-thinking the relationships between ministry and property owning, attention to both spiritual growth and justice matters, and cohorts of younger leaders not wedded to nostalgia for the 1950s.

What comes next? I couldn’t guess.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Comments are closed.