A Capitalist, a Democrat, and a Right-wing Christian Walk into a Bar

Several spiritualities conflict in the United States. Among the most prominent, sometimes doing battle and often shaping each other, are capitalism, democracy, and Christianity in its incarnation as the Christian Right.

Every society has a spirit and, therefore, a spirituality. By spirituality, I mean a set of beliefs and practices that orient persons and communities how to be and act in the world. A spirituality poses and answers questions about who we are and why we are. Spirituality is expressed in the orienting stories told, in setting the rules and boundaries for who belongs and who does not, in determining what is owed to each other, and in the offer of what the spirituality empowers participants ultimately to become.

Three examples. (There are many variations; please read the following as “types of” rather than as the only versions available.)

Capitalism includes a spirituality. Sociologist Max Weber’s most well-known and classic work is The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. He illuminated the affinities between Protestant Christianity, especially the Calvinist sort, e.g., seeking the assurance of salvation with a work ethic and thrift.

Today, one might say: capitalism offers the story that it is the only productive economic system that generates wealth and progress in human life. The worth of persons is determined by their ability to create markets and buy and spend within them. Wealth-creators are more valuable than everyone else. If you don’t have something to buy or sell, you don’t belong. Markets rule by their own rules and internal controls, and external intervention is, for the most part, detrimental to good order.

Liberty of corporations and of individual actors is of supreme importance. Markets can be brutal. Survival is for the fittest. Creative destruction is necessary for progress and to weed out the weak. The world’s development depends upon those who embrace and are willing to live with the risks and rewards of the profit motive.

And, I will note, contemporary finance capitalism and a consumer economy were two developments that Weber did not anticipate, at all, among the thrifty Makers and Savers about which he wrote. Weber might not have recognized the spirit of contemporary capitalism championed by the fictional Gordon Gecko, “Greed is good.”

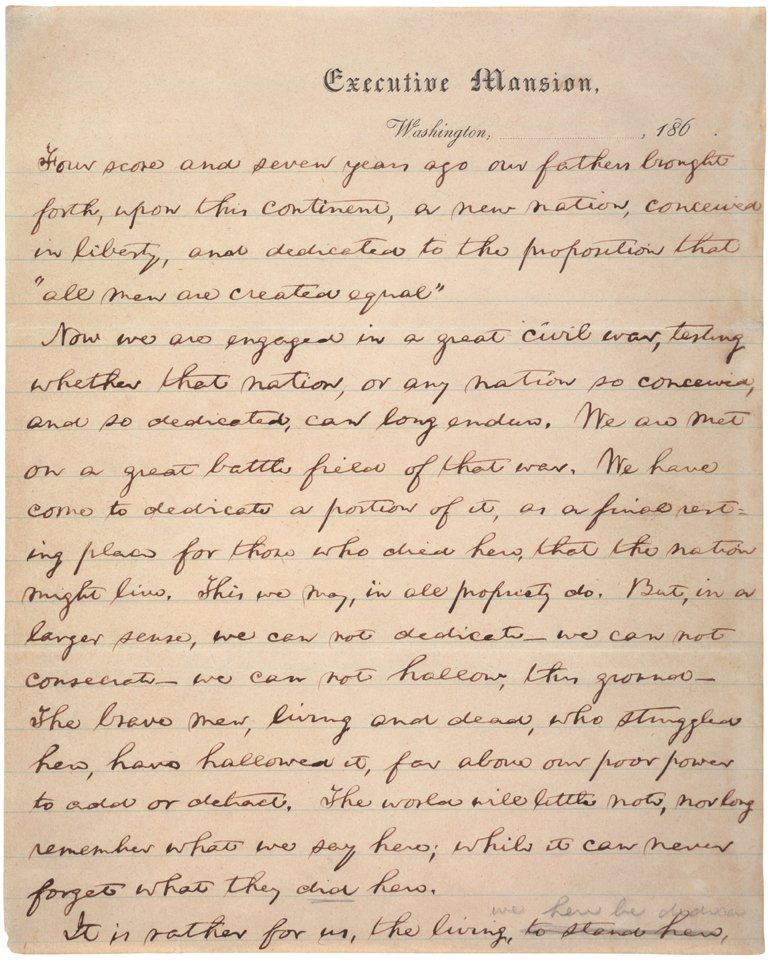

Gettysburg Address, First Draft

Democracy offers a spirituality. Let’s start with the line from President Lincoln: “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all (persons) are created equal.” In that juxtaposition of liberty and equality, one can see the roots of a story, rules for belonging, a social moral order, and an aspiration for a fully empowered nation.

A democracy dedicated to individual liberty resonates deeply with capitalism’s spirit. However, a democracy dedicated to the proposition that all persons are created equal clashes with a capitalistic market spirit which rewards the strongest, the most predatory, the most outstanding, and the most privileged. A nation and its government dedicated to the equality of all persons will constrain individual and corporate liberty when inequality reaches an intolerable level.

A nation and its government committed primarily to individual and corporate liberty may use “equality” as a carrot, as an incentive to participate in the market economy, but will not constrain liberty for the sake of greater equality. As we know from the historical context of Lincoln’s classic line from his address at Gettysburg, this nation fought a Civil War to limit the “liberty” of some persons to own other persons.

The fight for equality—as evident by policing, incarceration, health disparities by ZIP code, public school funding, mask wearing, Citizens United, and the immoral $7.25 minimum wage—is still not as evident as the maximization of individual and corporate liberty, at the expense of equality.

Every religious tradition is embodied and carried forth in a story, rules for belonging, moral order, and vision for empowerment that constitute a spirituality. For the past 40 years, the dominant religious expression in U.S. public life has been the political-religious alliance known as the Christian Right.

In this version of Christianity, God sent Jesus to die on the cross from the sins of the world. The saving power of that substitutionary atonement is accessed through the belief and confession that Jesus is Lord. Saving power is available only to individuals. Neither sin nor salvation is systemic. Goodness and grace, evil and damnation, are suffered individually—although damnation could be so widespread among individuals that a nation is imperiled.

God is a righteous Father who rewards obedience and punishes disobedience. This Father rules all the nations of the earth as King, and his regents are earth’s fathers and national leaders. There are strong affinities between the Christian Right and market capitalism, rooted in the devotion to individual liberty and choice. Those two spiritualities also share in rejecting government interventions to rectify inequalities. For the Christian Right, only individuals can make change. Bad systems don’t exist; they are a liberal fiction. There are no bad systems, only bad apples.

How different is a spirituality dedicated to fostering a more just, equal, compassionate society. A spirituality rooted in the equality of everyone created in the image of God and charged with caring for each other and the whole of the earth. A spirituality that attends to systems and cultures as well as individuals. A spirituality which understands justice as the primary social virtue and the pursuit of happiness in the context of what will help the poor and the vulnerable.

No one spirituality is sufficient to ground every aspect of a complex society. There will always be multiple strands woven into the braid that comprises a society. In times of profound social change and unrest, we can bet that the strands of spiritualities are showing and fraying. It is a good time to ask whether some strands need to be replaced. Or, at least, that is what I see.

Interested in a short-term, online, free course on this and similar topics? Check out Regenerating the Spirit of Democracy.

Dr. Gary Peluso-Verdend is president emeritus at Phillips Theological Seminary and is the executive director of the seminary’s Center for Religion in Public Life. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author. Learn more about the Center’s work here and about Gary here.

Comments are closed.